Richard Reishin Collins

Stone Nest Dojo, Sewanee

14 December 2025

People sometimes ask why we sit in zazen twice. Robert Livingston would have said, “because that’s what we do.” Which is a fine answer! Still, I’d like to elaborate on that. We once tried for a while to have three sittings of twenty minutes each instead of two thirty- or forty-minute sittings. We soon went back to two half-hour sittings. Why is it that two sittings work?

Think of nature, with its cycles from solstice to solstice. Think of the Dao, with form becoming emptiness, emptiness becoming form.

But first, think of the theatre.

Most plays consist of one act or three acts, although some, like Shakespeare’s, have five acts. But a one-act play is just a short three-act or five-act play, with the satisfying Artistotelian structure of a beginning, a middle, and an end.

Very few plays have only two acts, that is until Samuel Beckett came along with Waiting for Godot, which premiered in Paris in 1953. He understood that the Aristotelian structure was an artificial construct that played to our desire for an illusory completion, resolution, closure. But the two acts of Godot are closer to reality, they frustrate this desire, just as the existential experience of our lives can seem inadequate, unsatisfactory, what Buddhism calls dukkha (suffering).

All we get in Waiting for Godot is the middle, no beginning, no end. The first act opens on an ongoing situation, and the second act repeats and elaborates that situation, implying that a third act would be nugatory. But there is no third act, no completion, no resolution, no closure, no nirvana, just more of the same. Just like life. Just like Zen practice. And so we sit twice.

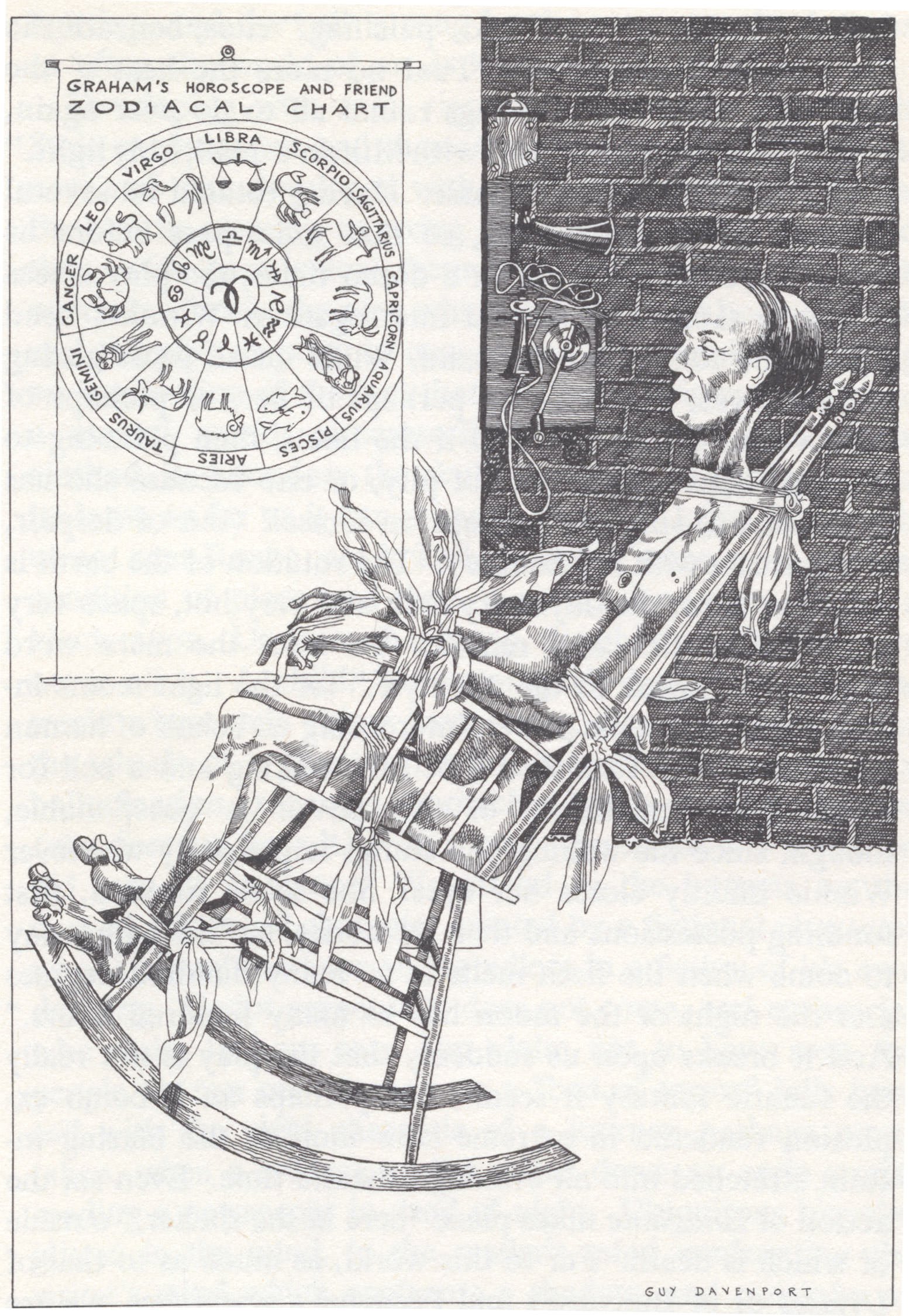

I am reminded of another Beckett work, his early novel Murphy (my personal favorite), which begins: “The sun shone, having no alternative, on the nothing new. Murphy sat out of it, as though he were free, in a mews in West Brompton.” It turns out that Murphy is sitting naked tied to a chair with seven silk scarves.

I like to think of zazen like that, tied with the silk scarves of our senses to our zafus, naked to our own consciousness. The natural world, like the sun, goes on around us, and we are more or less separate from it, as though we are free, yet we are tied to our zafus, or our chairs (chair, of course, in French means flesh) wherever we find ourselves, such as a mews in London, or a dojo in New Orleans or Sewanee. In this way we savor the stillness, the repetition, the nothing new.

This week we will have zazen on the day of the winter solstice. Solstice means “sun standing still” and has become an ancient universal symbol of the natural cycle of completion and renewal, emptiness and form. This is the turning of the Dao, when emptiness begins to become form, just as during the summer solstice, when form begins to become emptiness.

Completion and renewal is a nice definition of our sitting still in zazen, too. We can drop off the past, drop off the future, and sit still in the present moment here and now. People use this dark time to take stock of the past year and to look forward to the next year. What dead skin can I slough off, and what new skin will I grow?

Let your zazen be your solstice, your “sun standing still.” Calm in readiness, an ember in the darkness of the darkest day of the year. I love it when the logs in the fireplace seem to be spent, and then suddenly they flare up again, finding one last burst of energy before the body of logs is spent.

Guy Davenport’s illustration to Samuel Beckett’s Murphy