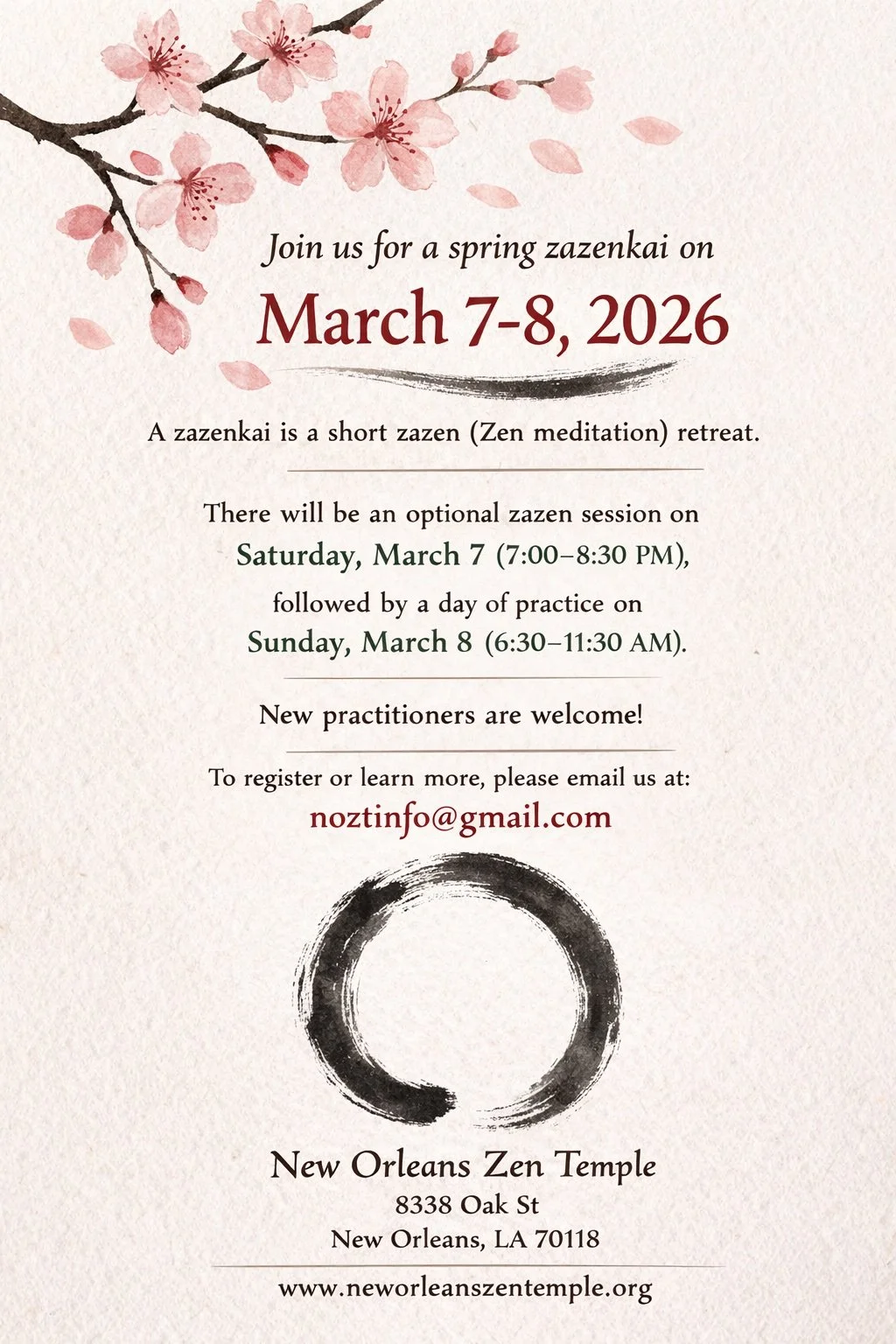

DELUSIONS ARE ENDLESS, WE VOW TO DROP THEM ALL

31 December 2025 / 1 January 2026

May this bell dispel

the delusions of all beings

everywhere.

Today, as we ring out the old year with the joya no kane ceremony, we are reminded that we live in a dream. The dream of the past, the dream of memory, the dream of attachments, the dream of success, the dream of failure, the dream of the future. Only in the present moment are we awake.

Thus we ring the bell on New Year’s Eve to dispel the 108 bonnos to clear our heads and hearts of the delusions of this year so that we can make room for the emptiness of the new year, with all its promise and potential. But as the second of the Four Great Vows reminds us, “Delusions are endless; we vow to drop them all.”

In the ordination ceremony we chant the Confession Sutra, the San Ge Mon, which lets us imagine that we can put aside a lifetime of past mistakes and misdeeds, which were the result of the three poisons—Greed, Anger, and Ignorance—and are the inexhaustible source of all delusion. We vow to consecrate our body, mind, and words to follow the true Way of Zen.

Of course these rituals are symbolic; they are not magic spells. We are still subject to the laws of gravity; still prey to greed, anger, and ignorance; still entangled in karma. But these rituals can be even more meaningful for this reason, and the results can be miraculous.

This year’s bell ceremony is particularly meaningful to me.

Ten years ago, at midnight, as 2015 turned into 2016, Robert Livingston Roshi met me in the dojo of the New Orleans Zen Temple, just him and me, for the intimate shiho ceremony, in which the teacher acknowledges the student’s transmission. Robert handed over his kotsu, the simple spinal-curved stick with the purple cord and tassel that is the symbol of the Zen teacher’s authority.

“But you will need your kotsu,” I said.

“Why?” he replied. “You are the abbot now.”

Robert was not one to hand over his authority lightly. In the past when he tried to do so, he soon took it back. Yet now he bestowed it with an alacrity that did not accord with the weight of responsibility that I felt fall on my shoulders. His retirement was complete.

As 2025 is about to turn into 2026, I look back and see how much has changed in a decade. Mujo, constant change, impermanence, is a key teaching in our practice. Yet it is always surprising how little we are prepared for it.

For the five years that followed receiving shiho, I took care of Robert and the temple until his death in the early morning of January 2, 2021. Since then, the temple no longer occupies 748 Camp Street, where it had been for thirty years. Now the temple has two locations, one in the bend of the Mississippi River in New Orleans, and the other high on the Cumberland Plateau in Tennessee. Muhozan Kozenji (Peakless Mountain Shoreless River Temple) is no longer a metaphor.

Our sangha has changed its appearance as well. We lost many of the old-timers who were uncomfortable with the transition to a new abbot and new surroundings. Change is difficult. But although the people come and go, the practice remains the same.

During the decade, hundreds of newcomers have passed through our dojos, some serious, some curious. I have ordained some 25 lay practitioners, a dozen monks, and two new teachers who have their own dojos.

We remain a sangha with a distinct flavor, a certain character, one that attracts highly independent individuals unafraid of discipline but suspicious of any organized religion, including this one. As someone from another sangha once said, not entirely inaccurately, “At NOZT they throw cubs off the cliff to see if they survive.”

Some things have not changed. We still practice zazen. We still hold introductions to Zen practice. We still have zazenkai and sesshin. We still chant the Hannya Shingyo, the Four Great Vows of the Bodhisattva, and the lineage in Japanese. Though our sangha is still small, our practice is vast. For it is none other than the authentic practice that Robert Livingston inherited from Taisen Deshimaru in the early 1980s and brought here from France.

Ten years from now, who knows what changes might be in store for us. I don’t know, but I suspect that we will still find a way—whether I am here or not—to continue to offer a place for those with the discipline and vision to follow the Way of Zen, which, as Deshimaru told his European students as he bid them farewell for the last time on his way to Tokyo where he died, is simply to do zazen éternellement, until we die.

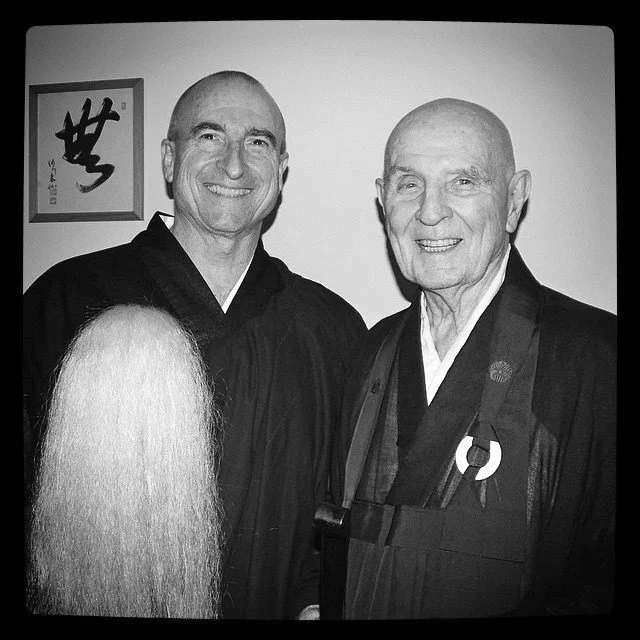

Richard Reishin Collins and Robert Reibin Livingston, January 1, 2016, New Orleans Zen Temple

LET ZAZEN BE YOUR SOLSTICE

Richard Reishin Collins

Stone Nest Dojo, Sewanee

14 December 2025

People sometimes ask why we sit in zazen twice. Robert Livingston would have said, “because that’s what we do.” Which is a fine answer! Still, I’d like to elaborate on that. We once tried for a while to have three sittings of twenty minutes each instead of two thirty- or forty-minute sittings. We soon went back to two half-hour sittings. Why is it that two sittings work?

Think of nature, with its cycles from solstice to solstice. Think of the Dao, with form becoming emptiness, emptiness becoming form.

But first, think of the theatre.

Most plays consist of one act or three acts, although some, like Shakespeare’s, have five acts. But a one-act play is just a short three-act or five-act play, with the satisfying Artistotelian structure of a beginning, a middle, and an end.

Very few plays have only two acts, that is until Samuel Beckett came along with Waiting for Godot, which premiered in Paris in 1953. He understood that the Aristotelian structure was an artificial construct that played to our desire for an illusory completion, resolution, closure. But the two acts of Godot are closer to reality, they frustrate this desire, just as the existential experience of our lives can seem inadequate, unsatisfactory, what Buddhism calls dukkha (suffering).

All we get in Waiting for Godot is the middle, no beginning, no end. The first act opens on an ongoing situation, and the second act repeats and elaborates that situation, implying that a third act would be nugatory. But there is no third act, no completion, no resolution, no closure, no nirvana, just more of the same. Just like life. Just like Zen practice. And so we sit twice.

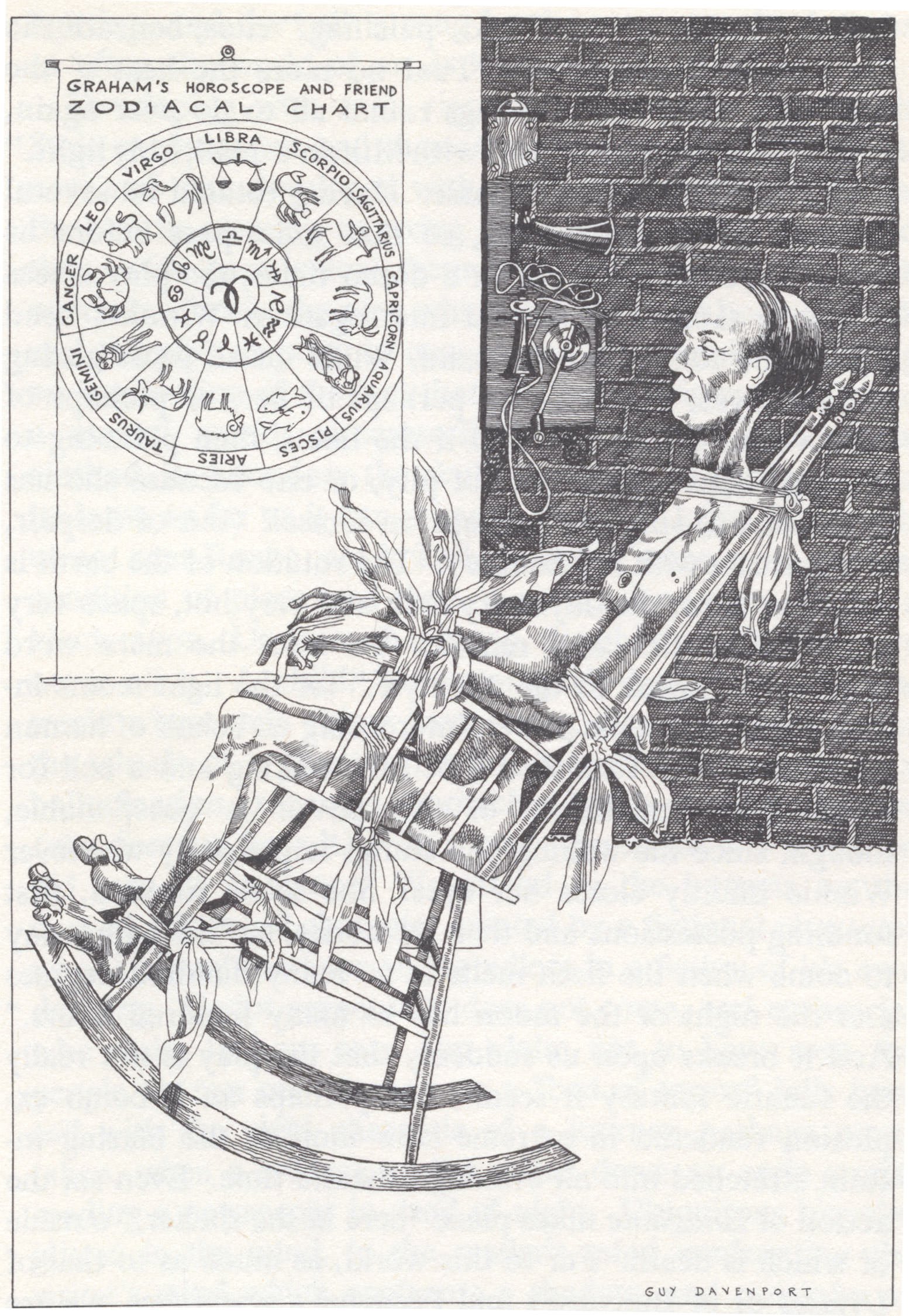

I am reminded of another Beckett work, his early novel Murphy (my personal favorite), which begins: “The sun shone, having no alternative, on the nothing new. Murphy sat out of it, as though he were free, in a mews in West Brompton.” It turns out that Murphy is sitting naked tied to a chair with seven silk scarves.

I like to think of zazen like that, tied with the silk scarves of our senses to our zafus, naked to our own consciousness. The natural world, like the sun, goes on around us, and we are more or less separate from it, as though we are free, yet we are tied to our zafus, or our chairs (chair, of course, in French means flesh) wherever we find ourselves, such as a mews in London, or a dojo in New Orleans or Sewanee. In this way we savor the stillness, the repetition, the nothing new.

This week we will have zazen on the day of the winter solstice. Solstice means “sun standing still” and has become an ancient universal symbol of the natural cycle of completion and renewal, emptiness and form. This is the turning of the Dao, when emptiness begins to become form, just as during the summer solstice, when form begins to become emptiness.

Completion and renewal is a nice definition of our sitting still in zazen, too. We can drop off the past, drop off the future, and sit still in the present moment here and now. People use this dark time to take stock of the past year and to look forward to the next year. What dead skin can I slough off, and what new skin will I grow?

Let your zazen be your solstice, your “sun standing still.” Calm in readiness, an ember in the darkness of the darkest day of the year. I love it when the logs in the fireplace seem to be spent, and then suddenly they flare up again, finding one last burst of energy before the body of logs is spent.

Guy Davenport’s illustration to Samuel Beckett’s Murphy

DONUTS AND DOJOS

Satori is like a thief breaking into an

empty house. There is nothing to steal.

—Kodo Sawaki

It’s just like at the office

when no one else shows

and there’s a box full of

Krispy Kreme all for me.

This morning an empty dojo

full of zafus and zazen

all alone with the cosmos

more donut holes for me.

Stone Nest, Sewanee —- 29 October 2025

KEEPING IN TOUCH

Kusen by Richard Reishin Collins

New Orleans Zen Temple

12 October 2025

You have all seen depictions of the Buddha in zazen, with his hands in the meditation mudra, as yours are now. I am sure you have also seen depictions of the Buddha with one hand raised in the mudra of reassurance or “no fear.” There is another important depiction of the Buddha with his right hand touching the ground called the bhumisparsha, or “earth-touching” mudra.

Buddhist mythology elaborates on this gesture to explain that this is his call to the Earth goddess to witness his triumph over the temptations of Mara and to verify his enlightenment at Bodhgaya. (As though the Buddha needed such certification!) One of the Japanese names for this mudra, referencing this story, is gōma-in (降魔印), or the “demon-subduing” mudra.

But do we really need the mythological narrative to explain what is obvious? Aren’t the Buddha’s fingers touching the earth at least as obvious as the finger pointing at the moon?

Pretty tale though the story of Mara and the Earth goddess is, the Buddha’s gesture is already clear and sufficient: his obvious and unmistakable way of telling us to keep grounded even as we seek spiritual enlightenment. After all, the most tempting of Mara’s delusions might be the lure of spiritual enlightenment itself.

This is why I prefer the more straightforward Japanese name for the gesture, shokuchi-in (触地印), simply “earth-touching.”

For Zen students, this mudra serves as a reminder that like rivers and oceans, we sit on the earth; like mountains and forests, we walk on the earth; like everything that arises from emptiness, we are earth. We are earth-bound creatures, even as our head touches the sky. This is zazen. In the posture of seated concentration, shikantaza, we become the living conduit between heaven and earth, between emptiness and form, between shiki and ku. We become buddha.

Deshimaru gives us a similar teaching about raihai (礼 拝), the ceremony that honors our connection to the earth with prostrations, laying our bodies on the ground in gratitude for and recognition of our extraordinary human existence, and for this extraordinary practice of zazen, where we are given the opportunity to defeat delusion (Mara) and escape suffering (samsara). This ceremony of touching the earth, says Deshimaru, completes zazen.

The word sesshin means, as you know, “to touch the mind (or heart).” We come to sesshin and through intensive practice with others we become intimate with the heart/mind (shin). In the beginning of our practice we tend to take this intimacy in a very limited way, as touching our own mind. This is the necessary first step, yes. But once we have become more intimate with our own mind, we can then become intimate with other minds, so that in our mature practice we touch not just our own mind but the mind of everyone who is practicing with us, and not just those practicing with us but, by extension, all beings, both sentient and insentient.

I once named one of our sesshin the “ses-sangha” to emphasize this larger contact with the others with whom we practice, not just those in this room, but all those in the Deshimaru sanghas, and not just those in the Deshimaru sanghas, but all those who have entered the stream. And not just those who have entered the stream of Zen practice, but all those capable of entering the stream of Buddhism. In other words, again, all beings.

Whenever I come to New Orleans from the mountains of Tennessee, I am reminded of the importance of keeping in contact with each other. Contact does not need to be constant, but it should be often enough to keep us awake and on the path. This may be daily or weekly, as in the local dojo or temple, or periodically as with our quarterly zazenkai and sesshin. Or it might be after much longer periods. The amount of time is not important. I can’t tell you how many times a former student has reached out to me after five, ten, or twenty years to say something like, “Now I understand what you meant when you said ‘Don’t move!’”

How, then, do we keep in touch when we are physically so far away? You know you can always reach out to me by text or email with your questions and comments about texts or practice. Since I have no curriculum for you, you must create your own curriculum, your own practice regimen. Since I have no exams for you, you must create your own exams. Zen practice is not like a college major: there are no set requirements spelled out for you in advance; you must spell them out for yourself. This is an independent study course. I am here to help you, but I cannot map your path. Only you can do that.

Just know that when you do zazen, you are already keeping in contact. When we keep in touch with ourselves, we keep in touch with each other. When we keep in touch with what is important, we keep in touch with the earth.

Whenever you do zazen, remember: you are doing zazen with me. Wherever you are doing zazen, you are doing zazen with everyone in this room. You are doing zazen with Robert Livingston, whose head presses the sky, with Deshimaru and Dogen and Daruma. You are doing zazen with the Buddha, whose fingers are touching the earth.

Smithsonian, 19th century

THE EIGHTFOLD PATH: MAP, MAZE, MARROW

Richard Collins, Abbot of Stone Nest and the New Orleans Zen Temple

QUESTION: I am wondering if you would be willing to offer some commentary on the Eightfold Path from a Soto perspective. Or maybe you can direct me to some foundational interpretations, possibly from others in the Deshimaru lineage?

ANSWER: I won’t speak broadly about the Soto perspective, nor for the Deshimaru lineage in general, but I can give you my own point of view informed by these traditions. I would refer you, first of all, to Dainin Katagiri's Buddhist Lay Ordination Lectures. While he does not deal there specifically with the Eightfold Path, what he says about the precepts might give you a sense of how I would answer your question. Taking the precepts (or the Eightfold Path) as literal or prescriptive is not helpful; if it were, one might as well go back to the comfort of the Ten Commandments and settle there. The Eightfold Path is not so narrow, at least not in Zen practice: it is an abstraction, a map with many possibilities, not an itinerary; it gives us recommendations, not commandments.

What I have in the last several years added to our Ordination Ceremony about taking the precepts is based on these Katagiri lectures (which Robert Livingston always assigned to new bodhisattvas to study before ordination, and I continue to do so). What is the opposite of "right" practice? (Or any of the other dimensions of the path?) The opposite of right practice is not wrong practice; it is literal practice, it is shallow practice. The opposite of wrong or literal practice would be subtle practice, nuanced practice, profound practice, realized practice, that addresses the reality of the present moment or situation, not some prescriptive dogma that tries to cover all situations.

Another way to think about this might be contained in the “repentance” part of our Ordination Ceremony. When we “repent” during ordination we do so absolutely, formlessly. What does this mean? It means that we are not repenting for anything in particular that we have done in the past because we are embracing our karma in total even as we cut it and drop it. Repenting about some particular action reinforces the separation between subject and object. Instead, we repent absolutely not only for past actions but for past inaction, for present actions and inaction, and for future actions and inaction. Formless or absolute repentance is exactly the quality of our zazen: no object and therefore no subject; no subject and therefore no object. No separation. Not repentance, in other words, in what we might think of in the Christian or Jewish sense, but “repentance in suchness.”

So you can see that in Zen practice a simple interpretation (or execution) of the Eightfold Path is not possible. What is Right Livelihood, for example? Does it mean we can't work in a bar? Does it mean we can't butcher meat? Such simple-minded approaches reduce the path to an either/or proposition, a narrow road bordered by steep cliffs on one side and bottomless abysses on the other, like Scylla and Charybdis. Any narrow-minded interpretation of the guidelines provided by the Eightfold Path reduces the journey to mere obedience to mere abstractions.

Zazen helps us to avoid the narrowness of dogma, opening up the possibilities of practice rather than closing them off. Some people want the precepts and the Eightfold Path to tell them what to do, to discipline them, but these guidelines, like the precepts, actually liberate us. They are not, indeed, instructions to be followed; they are, rather, what occur naturally, automatically, and spontaneously if we are harmonizing with our own path in the cosmos. They ensue.

We could also say this another way. The eight folds of the path need not be taken simultaneously. That is, if we can wholly dedicate ourselves to take just one of these seriously, we are on the right path, the path of right practice, which can only be our own unique practice. More importantly, one turn of the eightfold path naturally leads into another. There are three categories of the eight folds: ethical conduct (sila), spiritual/mental discipline (samadhi), and wisdom practice (pranja). Each is inextricably linked to the others, like some benevolent maze. If we practice Right Intention, for example, we are naturally bound eventually to come to practice Right Action, and so on.

You might remember the exchange between Bodhidharma and his four disciples when he asked for their understanding. The first three made their replies, and Bodhidharma said to them in turn, “You have my skin, you have my flesh, you have my bones.” But when Huike replied with a silent bow, Bodhidharma said, “you have my marrow.” All three had understanding, but Huike’s was the one that was formless, absolute, like Katagiri’s repentance in suchness

All Buddhist sects and all Zen lineages tend to emphasize one dimension of the Eightfold Path over another, morality over discipline, mindfulness over livelihood, etc. In the Deshimaru lineage, we emphasize Right Concentration, which could be seen as the last, or culminating, part of the path (if we take them sequentially or hierarchically). But Right Concentration can also be seen as the first, the doorway, “the dharma gate of bliss and ease,” as Dogen described zazen.

This is where we begin on the path, with zazen; it is also where we end. As Deshimaru instructed his European disciples when he left them for the last time, “Just do zazen, eternellement.”

Portland Japanese Garden, Oregon. Photo by R. Collins, 2020

SITTING IN THE STREAM

Richard Collins at the Fall Equinox Eclipse Sesshin

19-21 Sept 2025

My senior year in high school in Southern California I failed two classes, English and Social Studies. Two teachers, Mrs Holman and Miss Lahewn, made me a proposal: if I promised not to attend their summer school classes, they would give me a passing grade and I could graduate.

So in late summer, having hitchhiked north, I found myself sitting naked in a mountain stream that fed the Mackenzie River in Oregon, not far from where I was born. I was struck by the irony of the situation, being rewarded for my bad behavior by being given the freedom to explore my own path. But that was only the surface of the situation, the illusion.

A more profound realization was occurring as I sat in that shallow stream, one that would accompany me for the rest of my life.

As I set my book aside on the bank (I was reading André Pieyre de Mandiargue’s The Girl Beneath the Lion), I noted the clarity of the cold water coming down from the peaks and how the less I moved the more clarity crystallized. Silt settled. The rounded river rocks under the water emerged in sharp outline, colors muted but intense, rippling with insubstantiality just as the water seemed not fluid but solid, not a mirror but a magnifying glass into reality.

This, it occurred to me, was the still point of existence. Not the existence of the delinquent student, but rather the existence of what I would much later come to know as our “original face,” the one before our parents conceived us, the one before they were born. This realization was more than I could have expected from graduation day.

That experience did not reform me, not yet, but it did inform me that my path was to be different from the usual path, the path of the better (and worse) students in my graduating class, the obedient ones playing it safe and the ones without a cause heading for a cliff.

I had other moments of realization along the way, still points where the whole of life in all its complexity appeared to make sense I could not articulate. Then, when I came to Zen practice, I realized that these moments did not have to be accidental, that there was a way not exactly to seek them but to prepare for them, to allow these still points to emerge from time to time, knowing all the while that there were fluid stones at the bottom of this solid stream, this dream.

We call taking Buddhist vows “entering the stream.” I took formal bodhisattva vows in 2001, but I had unconsciously entered the stream long before that, fifty-five years ago, on the day of my in absentia high school graduation.

Gold Beach, Oregon

GIVE UP HOPE--SO YOU CAN GIVE FULL EFFORT by Preston Thomas

"Demand not that things happen as you wish, but wish them to happen as they do, and you will go on well." –Epictetus

Jul 27, 2025

I want to go a little deeper on a point from last week: the need to “give up hope,” as Charlotte Joko Beck recommends in Everyday Zen. Here is the original statement: “To do this practice, we have to give up hope.” As I noted previously, that sentence could apply to filmmaking, jiu jitsu, or any hard endeavor. It applies to life overall.

In short, our lives become miserable when we cling to the hope that everything will go as planned. We’ll land the perfect job. Find the perfect partner. Buy the perfect house. Everything will go great if we can just plan our lives meticulously and work our asses off; by the force of willpower, we will make the world line up with our vision.

Nope. Life doesn’t work that way. Nothing goes according to plan. Much of the wisdom handed down to us by the Stoics and the Zen and Taoist masters can be summarized in a few words: Life is as it is. Yes, we may have free will, but that does not mean that we control our lives or the outcomes of our efforts. Everything is impermanent. Nothing can be grasped.

What we do have control over is the effort itself. Shojin, in Japanese Zen parlance, refers to our willingness to apply great concentration and effort here and now in order to stay on the Path. If we can do that, we can break the cycle of inattention. In doing so, we can also liberate ourselves from the cycle of our karma and our bonno. “Karma” is our action and its circle of cause and effect; “bonno” is a broad term in Zen for human problems: issues, afflictions, and/or destructive and disturbing emotions—the psychological baggage that most of us carry through our lives.

Marcus Aurelius, in Meditations, writes: “How does your directing mind employ itself? This is the whole issue. All else, of your own choice or not, is just corpse and smoke.” Taisen Deshimaru—a Zen master in my lineage—says in the book Mushotoku Mind: “[N]othing is absolutely and definitively predetermined. All karma can be corrected once its energy is channeled into streams that are more favorable to the Way.” Echoing the Stoics, Deshimaru goes on: “Right practice of the Way requires a regular, well-ordered, well-considered life and a respect for duty.”

This shojin or effort—in the here and now and in accordance with our duty—is what allows us to tap into jiriki (the power inside of us as individuals). That is what allows us to make it to the end of an exhausting work shift, do one more hard round in jiu jitsu practice, or grab that final shot at the end of a grueling film shoot, when everyone is exhausted and wants to go home.

Life is a marathon and not a sprint, as both Stoic and Zen writers indicate. For instance, consider the years that go into making a creative project or preparing for an athletic competition. No meaningful achievement can be done in haste. We should adhere to the proverb of the Romans: Festina lente, or “Make haste slowly.” Everything emerges from daily effort, which starts here and now—in this moment.

It is not easy to change your lifestyle or your body-mind. Growth and evolution are not pain-free. They require you not only to show up and persevere, but also to concentrate and make a wholehearted effort every day, year after year. Yes, our lives may consist of short-term sprints as we push beyond our limits. Ultimately, however, these short-term sprints serve the longer-term marathon of life.

I know, in my experience as a filmmaker, martial artist, and Zen practitioner, that any sort of transformation or evolution is a very slow burn. Last week, I wrote about the creative process and used the metaphor of campfire embers—a fire continually burning itself out into smoking ashes. The embers have to be reignited constantly.

Sometimes, we have to burn out. We have to reach a breaking point, or at least come close—in work, art, sports, and life. The breaking point might not be a major external catastrophe; it might be internal, and it might be subtle. I like to call it the “fuck it” point. Once we pass that point, we can really thrive. The illusion of hope begins to fade. Our ego—which my Zen teacher, Richard Collins, compares to a sumo wrestler bullying us in our minds—starts to have less control.

We slowly come to let go of the vain notion that we are the masters of life. We finally stop resenting all of the disappointment in our lives and see it for what it is: a great teacher. Joko Beck calls disappointment “our true friend, our unfailing guide.” If we are unlucky enough to get everything that we want (or think that we want), we miss out on the teaching power of disappointment.

In other words, getting what we want all the time causes us to wander through life trapped in the illusion of our ego’s false hopes and ambitions. We will be reaffirmed in pursuing what Jason Wilson calls “shadow missions,” and we will continue accumulating karma and bonno. Baseless ambitions will dominate our lives.

Shadow missions obscure our true mission: life here and now. The work that needs to be done—whether that is teaching, creating, starting a business, or simply taking care of your surroundings and your community. Everyone’s mission looks a little different. However, we all have great jiriki or internal power. An ability to transform our lives and our surroundings. To find that ability, you have to look deeply inside of yourself. No one else can do that for you.

——————————

NOTE: Preston Thomas’s “Zen Jitsu” blog can be found on Substack at the following link:

https://prestonthomas.substack.com/p/give-up-hopeso-you-can-give-full?utm_campaign=email-half-post&r=1091a1&utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email

Jiu jitsu tournaments tend to go better for me when I detach from the outcome. Photo by Ponthus Pyronneau.