What follows are the memorial remarks made at Stone Nest Dojo on 10 December 2023 by Richard Collins, Abbot of the New Orleans Zen Temple, on the death of Aubrey LeBlanc.

Endless Journey

When the great Zen master Sengai (1750-1837) was asked by a parishioner for a blessing for his new baby, the old monk said, “May you die, may your children die, may your grandchildren die.”

I asked my daughter, when she was ten years old, what she thought of that blessing. She said, “Of course. Old people should die first.”

Yes, that is the natural order of things. Old people should die first. Parents should die before their children. Old monks should die before their students, too. So when a young member of the sangha dies, it offends the natural order.

This zazen is dedicated to the memory of Aubrey LeBlanc, who died suddenly last week at the age of 38.

I first got to know Aubrey some nine years ago, when I ordained her as a bodhisattva. She had been practicing at the temple on Camp Street for a while before that, but I was living in California at the time so I didn’t see her much on a day-to-day basis.

I arrived at the sesshin on a hot and humid July day in New Orleans. Robert, who was at the beginning of his long decline, had secluded himself in his room, where he stayed throughout the sesshin. He informed me, on very short notice, that I would be leading the sesshin and conducting the ordination ceremony. I was to brush the calligraphy on the rakusus and give the six new bodhisattvas their dharma names. Two of them were my students, but I knew very little about the others, including Aubrey, except that she kept to herself and seemed quite reserved.

During dokusan I attempted to get to know her a little better. Our conversation was brief but revealing. She was wary and guarded. You could tell she had had reason in the past to be distrustful. Still, I saw great potential in her, which is why I settled on the name KYŌHAN for her: “Shining Example.” She told me later that her self-esteem was so low at that time that she thought this dharma name had really missed the mark. “I could never be anyone’s shining example,” she said. But the name was not meant to be descriptive; it was aspirational, an encouragement, a conjuration, even; a hope; and, as it turned out, a prophecy since she did become an inspiration for others in their recovery from various addictions.

After that, she practiced at the temple on and mostly off over the next five or six years until she realized that Zen practice might really be integral to her path, just as important as her yoga practice, if not more so. This was due in part to her participation in Recovery Dharma.

She was very helpful as the sangha navigated the dharma gates of COVID and moved from the original Camp Street location to the dojo on Napoleon Avenue.

Her practice became strong in those couple of years, strong enough that I entrusted her to take the lead in introducing newcomers to the basics of the practice: posture, breathing, and attitude of mind. Her posture was exemplary, thanks in part to her yoga practice, and she soon mastered the various roles of Zen ceremony. And she always had searching questions during mondo that were helpful for others. Especially endearing to newcomers were her candor and sincerity in describing the arc of her practice and its influence on her recovery.

Her practice indeed seemed strong enough that I thought she might be ready to wear the kesa and kolomo and continue to be for others the Shining Example that she had become.

When she expressed doubts about being ready to make the commitment to monastic ordination, I said to her, “Life is short. What are you waiting for?”

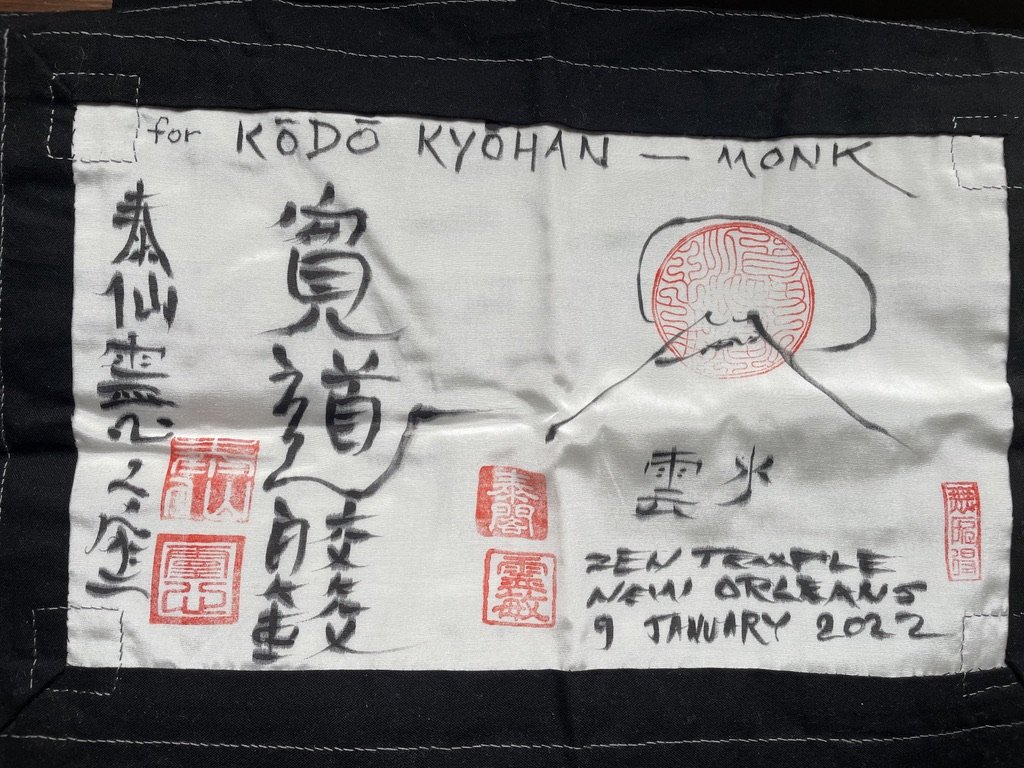

Her smile was glowing the day of her ordination, January 9, 2022, as I passed the monk’s kesa, rakusu, and kechimyaku over the incense and into her hands. And her grin when I gave her the monastic name: KŌDŌ. It was a tribute to Kodo Sawaki, Homeless Kodo, a similar name but not synonymous, with different kanji and a different meaning. His name means Ancestral Gate, while hers means Endless Journey.

Her monastic name was descriptive. Aubrey was an avid traveler, always setting off to Asia or South America, Thailand or Peru. These were not just physical journeys, they were spiritual journeys too. In spite of the early traumas of her life, she took these journeys on her own, a young woman traveling solo. She was fearless in that way. No, not fearless. She had an army of fears that haunted her. That was what was so admirable. She tried to face them down.

I didn’t see much of her in the final year of her life. She had drifted away from the temple and the practice, as people often do. After news of her death, I scrolled through the striking photos of her recent long trip to India and Nepal, which she had posted on Facebook. She seemed to have found a connection there; she seemed happy.

We can choose to use our bodhisattva name in daily life, and Aubrey chose to use her story to help others who had experiences similar to hers, to be a Shining Example. But the monastic name is not used until after death. Now Aubrey owns her monastic name. As we speak, her ashes are on the way to India, where she seemed to have found a connection — she always did feel an affinity with Kali, the goddess of Eros and Thanatos, the eternal cycle of Destruction and Rebirth. So her monastic name, KŌDŌ, or Endless Journey, takes on special significance now.

Gassho, Aubrey.

Gassho, KŌDŌ KYŌHAN.