You might hear from time to time the koan, “Why did Bodhidharma come from the West?” The answer given is something like, “The oak tree in the garden.”

When Buddhism came to China, it became more grounded in the phenomenal world, less airy. Not so many floating devas as Buddhism had in India, as a sort of hangover from the polytheism or henotheism of Hinduism. As Buddhism collided with Taoism, it became more realistic, more connected to nature, firmly planted in the here and now. It became Chan, and eventually Zen.

They are still up there, of course, the floating spirits. Take a look at the wonderful folk novel, The Journey to the West, or any martial arts movie, like the one I saw this week, The Sorcerer and the White Snake. These are full of magical transformations, transformations that these fantasies promise come from practice, defying gravity, logic, and the laws of biology and physics. It is not so easy to wean people of their addiction to the supernatural. We are children in that way.

Zen brings us back down to earth.

Bodhidharma is the face we give to this crux in the evolution of Zen. Bodhidharma as he was known in India, or Tamo as he became known in China, or Daruma in Japan. We say he came from India, sat for nine years in a cave at Shaolin, cut off his eyelids from which sprang tea leaves, and invented kung fu. This recognizable human figure is someone we can identify with. But of course changing centuries of belief took much longer than what could be done by just one person, it is a much more complicated process, just as changing the narrow path of Theravada or Hinayana Buddhism into Mahayana Buddhism, the narrow path into the broad path, was a much more complicated process than the effect of just one lifetime.

Yet in our Zen practice, this is exactly what is expected of us, changing our narrow path for the broad path, the little mountain getaway for the peakless mountain of Zen practice, the private stream for the shoreless river.

Fulfilling the Four Great Vows of the Bodhisattva path cannot be the work of a day, or a lifetime. Yet we can fulfill these vows every day if we don’t think of them in an abstract way but in a concrete, down-to-earth way

These vows may seem quite theoretical. But just as Bodhidharma planted Zen in China at Shaolin, we need to plant the bodhisattva vows in our own reality here in New Orleans, or wherever we happen to be.

The first great vow is – Shujo muhen seigan do – Beings however many they are, and they are innumerable, I vow to save them all.

Not only is that impossible, it doesn’t make a lot of sense. So it is much better to plant that as an oak tree in your own garden by finding a concrete equivalent in your life that makes sense. I am not talking about trees, of course.

What does it mean to save all beings? How can you do that? Simply by taking care of the things around you, whatever is in your power. Not just those things that are your responsibility legally or officially, but everything that you come in contact with, everything that your being affects. The zafu you’re sitting on, the clothing you wear, how you drive in the street, your pets, your family, your job, This is what it means to save all beings, Not to go around preaching the gospel of Buddhism or any other religion.

The second great vow is about bonno. Bonno mujin seigan dan – Illusions, however many they are, and they are endless, I vow to drop them all.

Bonno can be interpreted in many ways. Illusions, delusions, desires, problems, issues. But you must identify your own bonno, your own issues, your own oak tree in that sense. Your anxieties, your obsessions, your betes noires. What are the issues that you are going to drop? Don’t worry about everybody else’s.

Of course taking care of all of the beings that are near you might help to ease your anxiety or your obsessions, whatever your bonno happen to be.

The third great vow says that dharma gates – homon muryo seigan gaku – however many they are, and they are endless, I vow to penetrate them all.

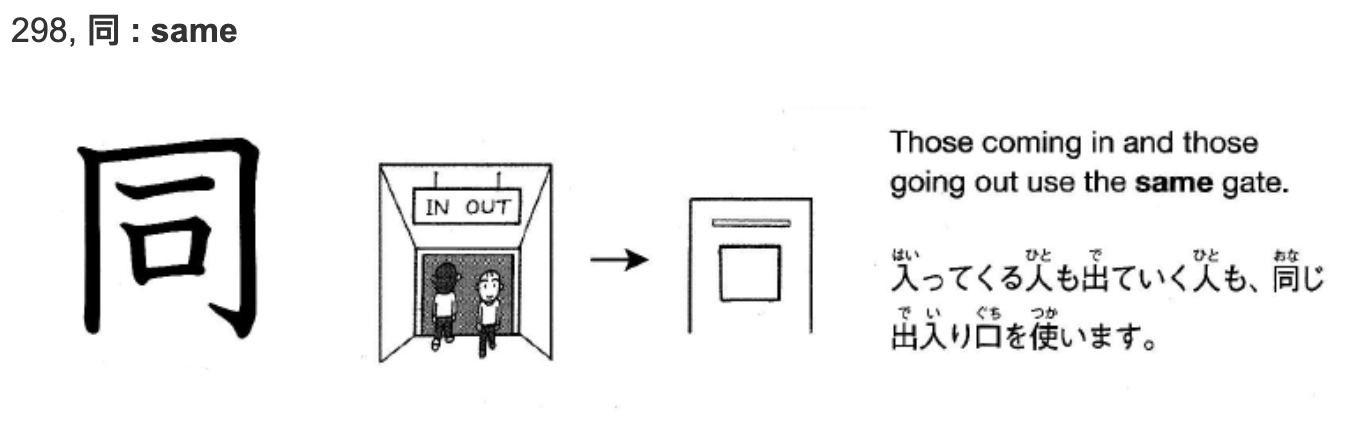

Dharma means many things. It means the order of things, the law, reality, the teachings, your own path or profession. Dharma is what unfolds; dharma is what falls into place. And the gates are a nice metaphor for the opening up of reality, or opportunity, or realizations, or clarities, epiphanies, satori.

Opening dharma gates – eliminating ignorance – can be very helpful in getting rid of your bonno born of the three poisons – anger, greed, and ignorance – very useful too in saving all beings.

But make it your own satori, not someone else’s. When a boy held up his finger to imitate Gutei’s silent answer to just about any question that he was asked, Gutei cut it off because the boy’s answer wasn’t his own oak tree.

The fourth vow has to do with the Buddha Way – butsudo mujo seigan jo – however long it is, I vow to follow through, and it is endless.

Here again, you have to discover what the Buddha way is, not from scripture, not from the sutras, not from what I’m talking about, but from your own experience, your own life story. Zazen: this is one Buddha Way, one proven path. But you can’t observe zazen, you can’t hold up your finger in imitation of a teacher. You have to do it yourself. You are the oak tree in the garden, firmly rooted in the posture of zazen.

But finding your Buddha Way is essential to entering dharma gates, helpful in dropping your bonno, and useful in helping all beings. This is why we put so much emphasis on zazen. It is the beginning of the path, but it is also the end. It is the One Great Vow that includes all the others, naturally, automatically, unconsciously.

— Richard Collins

Yakumo Nihon Teien Japanese Garden, New Orleans City Park